Despite the disclaimer on every advertisement for an investment product reminding customers that “past performance is no guarantee of future results,” most investors, and sadly many advisors use past performance as their primary criteria for selecting an investment. Like trying to drive a car by looking through the rear-view mirror, investing this way is likely to end badly.

Luck or Skill?

When I was in college, my intro to economics professor taught me a valuable lesson about predictions. He had all of the students in the class stand up. It was a large class of maybe 200 students. He told us he was going to flip a coin. He wanted each student to raise their hand if they thought the coin would land heads. About half the students raised their hands, and he flipped the coin.

If you guessed correctly, you were told to stay standing. If not, you sat down. After the first coin flip, about 100 students were standing. He repeated the experiment. Again, about half of the remaining students guessed right.

If you guessed correctly, you were told to stay standing. If not, you sat down. After the first coin flip, about 100 students were standing. He repeated the experiment. Again, about half of the remaining students guessed right.

Now 50 students remained. He flipped the coin a third time. Now 25 remained. A fifth time, now 12 or so were left standing. He flipped a sixth time. Now there were 6 left. A seventh time and there were 3 left standing.

An eighth flip and finally there was 1 student left standing. She had guessed 8 consecutive coin flips! What are the odds? Did she have a special talent or skill for predicting coin flips? Of course not.

The lesson is that when you are dealing with large numbers you expect to get some outliers. The same is true with investment managers. With literally thousands of mutual funds in operation, you are bound to get a few who manage to outperform the market for long periods of time purely by chance.

As an investor, how can you distinguish between luck and skill?

An Extreme Case

Take the case of Bill Miller, former manager of Legg Mason Capital Management Value Trust. He rose to prominence during the 90’s for his ability to outperform the market. In fact, he outperformed the S&P 500 for 15 years in a row from 1991 through 2005.¹ It was an unprecedented streak and brought him fame and fortune.

Sadly, from 2006 to 2010, his fund finished last among 1,187 US large-cap equity funds tracked by Morningstar. Dead last!

And so we are left to wonder, how much of Bill Miller’s record is due to luck and how much to skill? Is this a case of a skilled manager who lost his touch? Or is Bill Miller the girl in my economics class who happened to guess correctly eight times in a row?

Either way, we know this for sure – most of the investors in Bill Miller’s fund drastically underperformed the market. Seeing his streak of outperformance through the 90’s, the majority of his investors jumped on the bandwagon after most of the partying was over and suffered through the fund’s poor performance after 2006.

Winners don’t stay winners

As much as we’d all like to, we can’t buy a fund’s past performance. We can only buy future performance. Unfortunately, Bill Miller’s story isn’t an anomaly. Research shows that winning managers don’t stay winners.

In my last post, I showed that only 19% of mutual funds, were able to produce market beating results over the first 15 years of this century. We know that very few managers beat the market over time. But what if we chose only the best of the best? What if we only chose the managers who had a history of beating the market?

In my last post, I showed that only 19% of mutual funds, were able to produce market beating results over the first 15 years of this century. We know that very few managers beat the market over time. But what if we chose only the best of the best? What if we only chose the managers who had a history of beating the market?

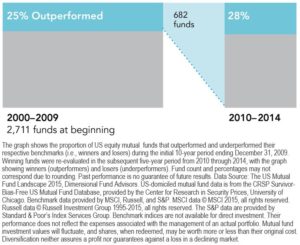

From 2000 to 2009, about 25% of managers of US equity mutual funds beat their benchmarks. As the chart below shows, if you had selected one of these “winners” you still had less than a 1 in 3 chance of beating the market over the next five years. In other words, winners don’t persist.

Moral of the story: The disclaimer “past performance is no guarantee of future results” is a wild understatement. It should be reworded to say something like “Past performance is highly unlikely to persist in the future.” If someone tries to sell you an investment based on its stellar performance over the last 3, 5, or 10 years, run!

Beware of Back-Tests

In the information age we live in today, a practice has cropped up that is even more sinister than selling past performance. This is the practice of selling hypothetical performance. These aren’t returns that a manager has actually achieved, they are returns that they could have achieved if they had followed a particular trading strategy over a specified time period – known as “back-testing”.

Of course, the past is one of the best indicators we have of what the future holds. Scientists use statistics to analyze data from the past and attempt to make predictions about the future. However, there is a big difference between good science and bad science.

Good science understands that occasionally you get an outlier that doesn’t actually describe reality – like the girl who predicted 8 consecutive coin flips. That doesn’t mean she’s psychic, it just means she happened to get lucky that day.

Bad science, in this case what is referred to as data-mining, digs into the data looking for anomalies. It doesn’t concern itself with statistical significance or economic rationales. The investment world is full of these anomalies. One particularly curious example is known as the Super Bowl Anomaly. Here’s how it works:

“A win by an original National Football League team—from the days when there was an NFL and an American Football League, before the 1966 merger pact—means the market will be up for the year. A win by a descendant of the AFL sends the market down. Teams created since the merger count for their conference, National or American.”²

As crazy as it may sound, this predictor has been correct 40 of the last 49 super bowls!

Of course, you’d be hard-pressed to come up with a sound basis for this anomaly’s existence. The point is, when you have a lot of data and a lot of computer power, it’s not hard to come up with a strategy that would have worked great over the last 5, 10, or even 20 years.

Look Forward, Not Back

Unfortunately, unless you can travel back in time, a strategy that would have worked in the past does you no good. What you need is a strategy that will work going forward. Such a strategy will have been tested with statistical rigor and have an economic rationale for its existence.

A discussion of such strategies and how to implement them effectively into your portfolio will be the topic of the next, and final, a segment in this series.

To schedule a complimentary, no-obligation introduction click here.

Sources:

¹Diana B. Henriques, “Legg Mason Luminary Shifts Role,” New York Times, November 18, 2011.

²William Power, “Super Bowl Stock Predictor Has a Streak Going,” The Wall Street Journal, January 15, 2016.